Martin Diamond

Contents

Background

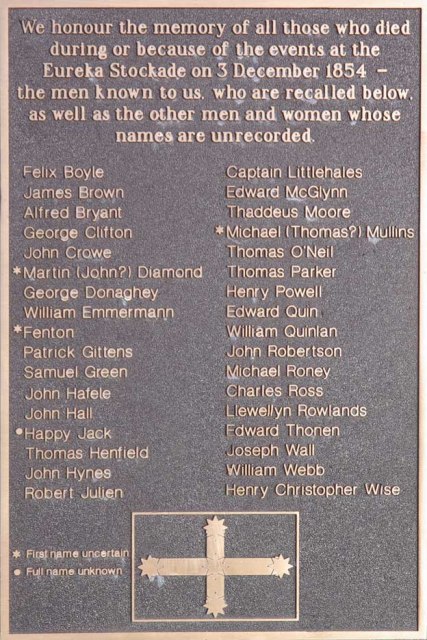

Martin Diamond (also John Diamond) was from Castle Clare, Ireland. He was born c1831. He died as the result of the Eureka Stockade Battle, and is buried in the Ballaarat Old Cemetery.

Goldfields Involvement, 1854

Martin Diamond owned a store on Eureka. According to John Moloney he was a rebel captain and had meetings in his shop on Thursday 30 November. [1] On December 3rd, 1854 he was shot by troopers inside his store and in front of his wife. Alpheus Boynton wrote in his diary, "The conduct of the soldiers generally through the whole has been anything but that of men, and some have brought upon themselves everlasting disgrace, for what true soldier would discharge his musket at an innocent and helpless female standing in front of her tent? and yet such was the case with some of the brutes clothed in uniform." Martin's wife, Anne applied for compensation from the government for property (to the value of £600 ) destroyed by the Military and Police at the time of the attack and stated in her application that her husband had been shot inside his store. Martin was born in Castle Clare, County Clare, Ireland and was only 23 years old when he died of gunshot wounds and was buried at the Ballaarat Old Cemetery. Giving evidence before the Goldfields Commission, Anne Diamond said, "My store was half in and half out of it [the Stockade] and I ran away, and I asked my husband to come, and he was coming after me, and he was shot and then they set fire to the tent." ....... " He then got three cuts of a sword and the stab of a bayonet." "After he was shot?" asked the Goldfields Commissioner. Anne replied, "Yes, they treated the bodies very badly."

The editor of The Times, Samuel Irwin, was the death informant.

In the News

- The Men Who Fell at Eureka.

- The list of killed and wounded at Eureka has never been complete, for many who escaped wounded died afterwards, ana some of the dead were taken away by their friends. The diggers' casualties as prepared by Peter Lalor, were as follows, from which it will be be seen that the majority who fell were Irishmen:— Killed — John Hynes and John Diamond, of County Clare; Patrick Gittens, Thomas O'Neil, and — Mullins, of County Kilkenny; Samuel Green, England; [John Robertson], Scotland; [[Edward Thoneman],] Prussia; John Hafele, Wurtemburg, Germany; George Donaghy, County Donegal; Edward Quin, County Cavan; Thomas Quinlan, Goulburn, N.S.W.; a digger on Eureka known as "Happy Jack;" and two others whose names were unknown. Died of their wounds — Lieutenant Ross, Canada; William Clifton, Somersetshire; Thaddeus Moore, County Clare; James Brown, Newry, Ireland; Robert Julien, Nova Scotia; Edward McGlyn, Ireland; two men whose surnames were Crowe and Fenton; and another quite unknown. Twelve men who were wounded are known to have recovered. Of the attacking force, three privates were killed in the assault, and Captain Wise and another private died of their, wounds.[2]

- GOLD-SEEKERS OF THE FIFTIES. - THE LEADERS OF EUREKA. MEN AND MOUNTEBANKS.

- Every great fight has its heroes. The historian is sometimes silent as to them, but in long after years, when time has ripened to their opportunity, when the weakened memory of the living and the silence of the dead have made corroboration vague, they come from a modest retirement, and admit their prowess. Eureka is the great est of Australian fights—in fact, the only fight—and it too has its worthies. Their deeds, like those of Falstaff, grow in the recital. Thus quite a hundred men were standard-bearers at Eureka, and carried the Southern Cross. Quite half as many sheltered Peter Lalor, scores nursed him, and a dozen at least escorted him through the bush to Geelong when there was a price on his head. It would be cruel almost to disbelieve these men, for by long practice many of them have come to believe themselves. But this element of after- romance has made the telling of the story of Eureka somewhat difficult. It was ever a delicate matter to handle, for the motives of those who fought on Eureka Hill were as wide as their nationalities. The one great purpose—resistance to the gold license and the detestable practice of digger-hunting—may be freely recognised. The worst of it is that those who look upon the men of Eureka as being all brave, high-minded, high-souled reformers will see no other motive than this one; while those who hold by the law admit it as the last motive of all. They see in Eureka only the desperate resource of a band of rebellious agitators. Either of these extremes misses the mark, but the prevalance of party statement renders it difficult to sift the wheat from the chaff, and makes it essential almost that one should skip controversial matter in telling the story of a desperately foolish but all the same a gallant undertaking.

- The foreign element was largely mixed up in Eureka—it did most of the talking and boasting, but, as often happens in such a case, least of the fighting. In the runing it was foremost. Some of the men who fought there knew it, and, as Mr. John Lynch says, were impressed when the brave, kindly old general, Sir Robert Nickle, who had often led the Connaught Rangers, said, "I would rather have you Irishmen before Sebastopol than in a thing like this. Why didn't you Britons settle your differences between yourselves, instead of allowing foreigners to meddle in your domestic affairs?" Yet not all the foreigners ran, for some of them died bravely and like men under the palisades of Eureka, seeing through to the bitter end that to which they had put their hand. The story of Eureka, the fight, the flight, and all connected with it, cannot be told in a single article. The better way, perhaps, were to begin with a few words as to the more picturesque of the men who figured in it.

- Highest of all in the group looms the figure of Peter Lalor, whose after-prominence in Victorian political life commemorated by a statue in the main street of Ballarat, has made him the one man whom very many people to-day are able to associate by memory with the Eureka fight. He came to Ballarat first a young, stalwart, handsome Irishman, standing nearly 6ft. in height, with dark brown hair and beard, the firm upper lip and powerful neck always clean shaved. In manner a quiet, unassuming young fellow, with the air of an educated, well-bred man, he at first took no part in the agitation, and only came prominently into notice when, after the formation of the Diggers' Reform League, a fighting leader was required, and fighters, as apart from "spouters," had become suddenly scarce. Lalor was a man who neither by training nor disposition was inclined to turn the other cheek. His family was a historic one in Queen's County, Ireland, tracing back to the chieftains of Glenmalure and Slievmargy. His people had been patriots or rebels—as you please—from the time of the Tudor intrusion, and his father, a member of the Imperial Parliament, was a follower of O'Connell. The speech in which Lalor took command of the men of Eureka was essentially a manly one. "I have not the presumption," he said, "to assume the chief command, no more than any other man who means well in the cause of the diggers. I shall be glad to see the best among us take the lead. If, however, you appoint me as your commander-in-chief I shall not shrink. I mean to do my duty as a man. I tell you, gentlemen, that if once I pledge my hand to the diggers, I will neither defile it with treachery nor render it contemptible with cowardice."

- There was a time just before Eureka when two currents of public feeling which had hitherto followed the same channel diverged. Peter Lalor headed the more turbulent stream; the milder followed the lead of John Basson Humffrey, a man who took no part in the rebellion, but was a recognised leader in the agitation which led up to it. He was a mild man who opposed the extreme step, and thought the end would be gained by legitimate agitation. It required courage to give such counsel then, for one man named Frazer who advocated it at a meeting on Bakery Hill would have been torn to pieces but for the inter vention of the chairman. Humffray has been described by one of his compatriots as a man "with a quiet sort of John Bull smile." He was in turn exalted as a hero and denounced as a traitor, and the term "Apostle of Peace" was applied to him in anything but a complimentary sense. He saw the folly of armed resistance, the use-lessness of burning licenses, through which policy the diggers thought every man on Ballarat must be arrested and the camp overwhelmed with prisoners. It has been urged that Humffray, as a leader, went too far if he were not prepared to take the extreme step, and it is a fact that up to the last he was expected to assume command. From beginning to end he was, however, a man true to the diggers' cause, and who fought for it according to his lights. When years afterwards representatives were required for Ballarat the two men chosen were Lalor and Humffray.

- Every tragedy has in it some elements of burlesque. That of Eureka was largely supplied by two foreigners—Colonel C. H. F. de la Vern, a Hanoverian, and Signor Carboni Raffaello de Roma—an Italian. The names and titles take up some space, but they are worth it. As often happens with mountebanks in the same line of business, the two cordially detested each other, and so one gets at their real characters.

- Vern was a long man, whose legs were so obviously made for retreat that they took the initiative, and carried the gallant fellow off over the back of the stockade the instant the first shot was fired. A captain of pikemen who saw him run called on someone to shoot him, but Vern was too good a sprinter. He claimed to be a military strategist, and a specialist in fortification. The only strategy he displayed was in leaving hurriedly for the Warrenheip Ranges, and the Eureka Stockade, the outcome of his skill in fortifications, was a howling farce. It had been designed on the basis that the troops would attack from one direction. But, as troops often do, they came over at the back, where there was no protection worth the name. One great and undeserved honour was paid to Vern. Imagining him to be a leader, the Crown offered £500 for his arrest, and only £200 for Lalor. Vern had really expected to be leader, and sulked when the young Irishman was appointed. He talked much of a German legion he had enrolled, and which was to rush to arms the minute the Southern Cross waved from Eureka Hill. This was the original legion that never was listed—at least nothing was ever heard of it.

- His rival, Raffaello, was something less of a poltroon perhaps, but still one braver in argument than fight. He was a fiery little Vesuvius, who at the meetings moved everything in the direction of extremes. The "hated Austrian rule" was dragged into all his speeches, and he claimed to have fought under Garibaldi. He had seen so much of active service, indeed, that when it came to fighting at Eureka he graciously allowed others to get to the front for their baptism of fire, and retired to the shelter of a well-built turf chimney, the best protection against bullets that the stockade afforded. He has written a book on Eureka—a wild mass of rodomontade that reads very curiously now. It begins with the magnificent assertion, "I undertake to do what an honest man should do, let it thunder or rain." He announced his book for sale at Eureka "from the rising to the setting of the sun," on the anniversary of the fight, and there publicly mourned his ost comrades and the lost cause—quite oblivious of the fact that through Eureka that cause had been won. He appears to have had an Italian eye for small economies, and on leaving Ballarat a prisoner, he wept, not for the poor fellows he had talked to their death on Eureka Hill, but for the loss of his tent and puddling machine. He was known as "Great Works," a pet phrase of his—but Great Talks would have been much more appropriate.

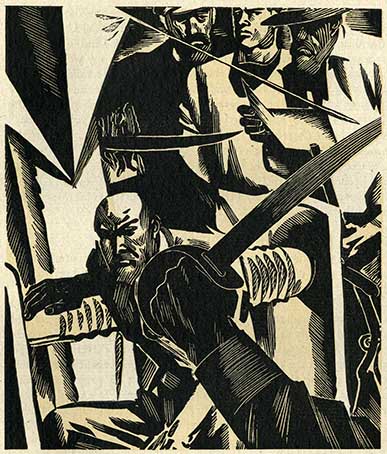

- It was not so with all the foreigners, though. In the rank and file were men who fought well. Few were better known on Ballarat than Edward Thonan, the poor Prussian lemonade seller, who carried his keg around amongst the claims. He stood to the brest-work till a bullet passed through his mouth and killed him. Another big German blacksmith was busy within the stockade forging pikes and spear-heads for days before the fight. As the soldiers came over the stockade with a gallant rush, the big German, fighting bravely, picked out Lieutenant Richards, and made a dash for him, but the officer, in fair fight, ran him through and killed him.

- It is a curious coincidence, indeed, that nearly all the orators of Eureka cut a poor figure in the fight. Some apology is needed for mentioning them at all, but they were picturesque characters in the life of the time, unlike so many of the silent fellows who simply took the post given them and fought till they were overwhelmed. One of the fiercest of rebels up to a certain stage was Thomas Kennedy, a voluble little Scot, whose large aim in life was the regeneration of mankind. He had all the attractive phrases of the Chartists on his tongue, a remarkable facility for making speeches that were rarely to the point, but which breathed always resistance to the death. A favourite couplet in his platform address was—"Moral suasion is all a humbug, Nothing convinces like a lick o' the lug."

- No one's "lug" tingled from any blow struck by Mr. Kennedy at Eureka. One of his last outbursts before the battle was:— "On, on, my brave comrades; before to- morrow's sun shall have set Victoria willhave lost one of the brightest jewels in her crown." He flourished a sword as well as a tongue in quite a tremendous way, but before a shot was fired became, it is said, absorbed in a pipeclay drive at the bottom of a disused shaft, and so missed the chance of striking that blow in revenge for his murdered mate Scobie, of which he had so often boasted.

- Another very voluble—if not in the fighting sense valuable—man was Timothy Hayes, who acted as chairman at the diggers' meetings, and was to have hammered home bullets behind the palisades as deftly as he did arguments on the platform. Mr. Hayes had a turn for rhetoric, a strong partiality for such sonorous defiance as— "The sun shall see our country free, Or set upon our graves."

- His last speech before the fight wound up with the fateful words, "Are you prepared to die?" Mr. Hayes was apparently not quite prepared. It may have been his misfortune, though, rather than his fault—for men came to the stockade and left it as they pleased—that at the time of the fight he was absent without leave, and took no part in it.

- So much has been said of the mounted banks of Eureka that the belief may gain ground that they were a majority. If puerile, they were, as has been said, picturesque, hence the prominence given to them.

- If one man on Ballarat had more right than another to protest against gold-getting being made difficult, it was surely James Esmond, the first discoverer of gold in Victoria—not a chance discoverer either, as one who stumbles upon a nugget in his path, but an observant man, who applied the experience he had gained elsewhere. He was a quiet man, who said little, thought a great deal, and backed up the opinions he held with a stern, resolute courage. Such men were plentiful enough at Eureka, in spite of the buffoons and charlatans who aspired to lead them. While others were talking Esmond set to work, so that the miners who meant to fight might be properly armed for the encounter. Another of much the same mould was John Manning—a very fine fellow indeed, but a man who would stand no nonsense. Equally honest and earnest was the like- able Lieutenant Ross, a Canadian, and one of Lalor's captains at Eureka. His one wish was to resent as men the insults to which the diggers had been subjected. He fought well in the grey dawn of that Sunday morning until he was shot in the groin and died soon afterwards of his wounds.

- No one in Ballarat to-day needs to be told of what stamp of man Mr. John Lynch, the well-known surveyor, Smythesdale, is. None more upright, loyal, and honourable—yet he, too, fought under Lalor at Eureka. He lives to tell the story now, probably because he took the precaution when manning the palisade to close up the open spaces with some of the loose planks lying about. "How the fight was to benefit us," he explained, "I never could see. But then, like others, I didn't moralise over the matter at all, but just took out my miner's right and burned it." Mr. Lynch on joining was told off to the Californian Independent Rifle Brigade, most of whom were only armed, though, with revolvers and knives. It was commandered by James McGill, largely on the strength of his own statement that he had had a military education at West Point. He left his Californian Rangers to fight without the help of his skilled control, for he, too, was absent without leave. There was one Shanahan, in whose tent the councils of war were held, but that fact did not inspire him to valour, for he took refuge behind a bag of flour, which was quite bullet-proof. A contrast was Patrick Curtain, captain of the hopeless, helpless Pikemen, whose share in the fray was just to be shot at, and Thaddeus Moore, who had a bullet through both his thighs, and died of his wounds. John Robertson, a pugnacious Scot, fell full of wounds, and, being somewhat like the Italian Raffaello, those who found him said, "Poor Great Works, he had some fight in him after all." "Their joy on finding I was not dead," says the Italian himself, "was pleasing to me." Robertson didn't count for much—except as a casualty. The first man wounded at Eureka was a miner named Downes. He was fighting alongside John Lynch, and staggered back, with a bullet through his shoulder, crying out "I'm shot!" "Don't worry," said his comrade, "that may be all our case soon," and just at the instant John Diamond rolled away from the palisades— dead. Some who died at Eureka were known by not even a name to their leaders. One of them has come down to us as "Happy Jack," while a big blackfellow, whose name and fate are alike a mystery, has been described as one of the pluckiest fighters in the Stockade.

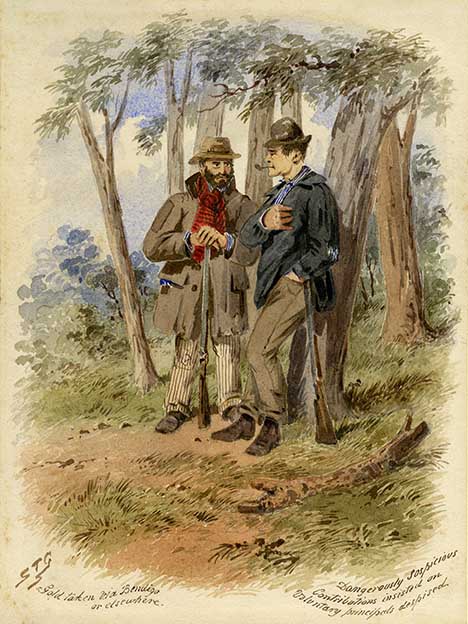

- One name has often been mentioned in connection with Eureka—Raffaello's book teems with execration of it—the name Goodenough. The business of a spy, though a detestable one in popular fancy, was a task that in this case demanded nerve. Goodenough was a sergeant of the forces, who went in with the miners to spy out their works, and it was because of his reports as to preparations at the Stockade that the sudden night surprise was determined on. Sergeant Goodenough took his life in his hands, for had his mission been suspected he would have been hanged on the flagstaff of the Stockade. When all is said, indeed, the name of Goodenough comes down out of the distance with far less of contempt than upon those who execrated it—empty-headed, noisy charla- tans such as Raffaello and Vern. [3]

See also

Further Reading

Corfield, J.,Wickham, D., & Gervasoni, C. The Eureka Encyclopaedia, Ballarat Heritage Services, 2004.

References

External links