Henry Nicholls

Contents

Background

Henry Richard Nicholls was born in 1830 in Regent street, London, England.[1]

Henry Richard Nicholls was active with London Chartism. Nicholls was known both as a lecturer and poet before he emigrated in 1853 at the age of 23. He became assistant editor of the Gold Digger's Advocate, but unlike his editor, George Black, was an atheist. He is credited with introducing "a flavour of the cosmopolitan radical milieux" of London to the paper, with letters from the Italian republican Giuseppe Mazzini and Hungarian nationalist Lajo Kossuth running alongside Chartist poetry and editorials on republicanism and temperance. The paper failed in September 1854 and Nicholls moved to Ballarat, where he became a gold miner and correspondent for the Melbourne Argus. Nicholls died in 1912.[2]

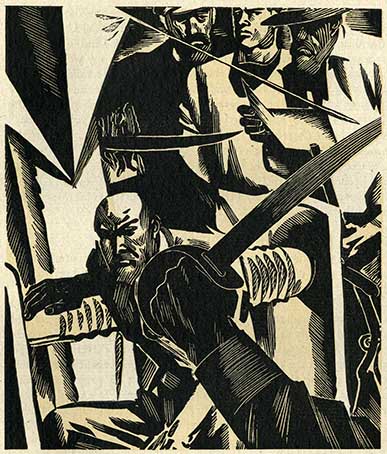

Goldfields Involvement, 1854

Nicholls was editor of the Diggers' Advocate newspaper with George Black, an ardent Chartist. Nicholls entered the Eureka Stockade on Friday 1 December 1854. In his written account he states that on Saturday night many stockaders were drunk.[3]

- REMINISCENCES OF THE EUREKA STOCKADE BY H.R. NICHOLLS - As night drew on there was a steady falling off in the numbers. One after another went away to get a clean shirt or to prepare in some way for Sunday, although there were rumours which grew more frequent as the night wore on, that an attack was to be made on the stockade. At night these rumours seem to have caused increased caution, for pickets were posed far out towards the camp, so that any advance of the troopers and the soldiers might be made known and be prepared for. By ten o’clock in the morning I should say that there were hardly more than a hundred in the Stockade. Many of these were Irish and, indeed, the movement at that time seemed to have become almost an Irish one. At this time egress from the enclosure was stopped without a password, but why I never was able to learn. I, with others, about ten o’clock went out – I do not remember that we were sent – to see if the pickets were on duty. We were, in fact, a sort of ground round. After a time we found the pickets in a groghut playing cribbage, and drinking, and, apparently, in the best of humours with themselves and conversed with a young lady, decidedly good looking, who presided over the grog. By this time it must have been drawing on for midnight, and we returned to the Stockade where there were again rumours of an attack, but how originated no one could tell. By this time I began carefully to consider, taking an accurate survey of the whole encampment, and I came to the conclusion that, at that time, at all events, there were not the means of a successful fires, except two big Irishmen with gigantic pikes, who appeared to derive great pleasure from guarding the place of exit. I told my brother that it was but wisdom to go and see what the next day would bring forth, to which he demurred at first, but finally saw the prudence at first, but finally saw the prudence of the opinion I had formed. So we essayed to leave, but the pikemen would not let us. They enforced their orders with quite an air of vigilant duty, saying that we must get the password from him, which I found to my amazement was “Vinegar Hill”. This satisfied me at once, and I decide to go him. We gave the word, the pikes were lowered, and forth we went to make out way to the Red Hill, where, on the main road, our tent was pitched.

- At this stage, once more, I found the value of that bump of caution which I am said to possess. The time was about two o’clock on the fatal Sunday morning, December the 3rd, 1854. It was a true Australian night, not a breath of wind stirred the leaves of the stringy-bark trees, which then grew thickly on the ranges, or of the gums whose white stems gleamed ghostly on the flats as we passed” The moon shines bright on such a night as this”, we might well have sighed our souls to some fair dweller in a tent, after the fashion of Troilus, albeit the tents enclosed stalwart males mostly, sleeping after a hard day’s work in search for fold, or, possibly, in marching and counter marching. The whole air was full of that fine haze which is seen on such nights once or twice a year, a haze which slightly veils but does not conceal, lending a ghostly, yet be beautiful appearance all around. Our road lay properly in the direction which might have brought us into collision with any outlaying parties from the abode of the authorities. Bearing in mind the rumours of an attack I decided to make a long detour, so shifting off to the left we wound our way through the trees and the holes till we reached the main road to Geelong. It was lucky that we did so, for, as I afterwards learned, at that very time the troopers, who were very furious and reckless, were issuing from the Camp, and if they had seen us with our guns upon our shoulders we should have had, I fancy, small mercy on that day and at that hour. As it was we met with no one. The most profound silence prevailed; no lights were to be seen; the whole visible would was at rest. As Wordsworth says about the houses, the very tents seemed to be be asleep, and yet at that very time was being prepared the attack which was to cause the loss of thirty or forty lives, and change, let us happily remember, the Government of Victorian goldfields. For ourselves, we reached our tent where some of our mates lay fast asleep; all except the sailor, Bill, who had elected to remain in the Stockade. Wearied out we lay down and knew no more till about five o’clock in the morning when Bill rushed in, declaring it was all over, that he had barely escaped, and seizing his clothes he vanished never to be seen by me again.

- A few things remain to be told. The next day all was silence. Troops and sailors arrived from Melbourne under the command of Sir Robert Nickle, martial law was proclaimed, and there was a demand fro special constables. One man only was sworn in, for all were with the rebels, so-called, although many thought that there was no necessity for, nothing but folly indeed in, an appeal to arms. On the second day, however, in spite of the martial law, it was decided to hold a public meeting, which was held, as the authorities wisely saw that they had to deal with loyal yet injured people. Resolutions were passed in favour of amnesty and I and my brother, sitting on the top of the Black Hill, drew up the petition which was subsequently presented, and was successful.

- A few nights afterwards I visited the grog-tent out of which we had turned the defaulting pickets, where there were was a young and pretty girl, who attracted much attention in those days. This tent was but a short distance from the Stockade, but was not burned down as so many were. The girl told me that on the morning of the attack, when the Stockade had been rushed, the tent was full of fugitives – some lying on the ground, some under the tables, and all afraid that they would be discovered. She stood outside, and when some troopers came up she told them that she was alone, and hoped that they would not hurt her. One excited soldier, she said, ran his bayonet through her dress, but the others called him away, and the tent was not entered. So the fugitives escaped, and were thankful therefore. This is what I know about the Eureka Stockade.[4]

- OBITUARY: Mr. H.R. Nicholls, editor of the ' Mercury," Hobart, died suddenly last evening at the age of 82 years. He has been away from his office during the last few days, suffering from an attack of influenza, and heart failure ensued. Mr Nicholls has been editor of the "Mercury" close upon 20 years, and was recognised as in the front rank of Australian journalists. "John's Notable Australians" gives the date and plane of his birth as January 6, 1830, in Regent-street, London. He was educated at Binfield (Berks) Collins' School, and the Literary Institute, London. He came to Australia in 1853, settling in Victoria, where he edited "The Diggers' Advocate." Afterwards he was mining reporter and leader writer for the "Ballarat Times;" then editor of the "Ballarat Star," and subsequently leader-writer and essayist on the "Argus" and the "Australasian" for many years, and on coming to Tasmania acted as correspondent in this state for both those journals. The element of adventure 'was not wanting in his career, for he was in the Eureka Stockade, drew up the petition for amnesty, and was elected a member of the first local court at Ballarat. Last year Mr. Nicholls was very prominently before the public, for around him centred a memorable fight in the cause of the freedom of the press. He was charged by the Attorney-General with contempt of court in connection with certain criticisms of Mr. Justice Higgins, under the heading 'A Modest Judge." But the case was dismissed by the High Court. After the verdict Mr. Nicholls was tendered a public reception at Hobart, when eulogistic reference was made to his work and his services to the community. Deceased leaves a distinguished son in the person of 'Mr. Justice Nicholls. Our Melbourne correspondent wired last night:-"The 'Argus' says that Mr. Nicholls' death removes from an active sphere in journalism one who in Victoria and Tasmania has been held in the highest regard by his colleagies of three generations."[5]

Post 1854 Experiences

Nicholls became a member of the Local Court at Ballarat to which he was elected on 14 July 1855. [6]

Obituary

- Mr Henry Richard Nicholls, editor of the Hobart "Mercury," died in his 83rd year last week. Mr Nicholls was in the Eureka Stockade, and had a brilliant literary career. [7]

- OBITUARY. - MR. H. R. NICHOLLS, EDITOR OF "THE MERCURY." - HIS INTERESTING CAREER.

- It is with deep regret that we announce the death of Mr. H. R. Nicholls, who for the last 29 years has been editor of "The" Mercury." Mr. Nicholls, who has not for some time been in robust health, had an attack of influenza on Sunday, and early yesterday evening succumbed, at the age of 83.

- Mr. Nicholls was horn in Regent street, London, in 1830. His father's house was close to Buckingham Palace, and Mr. Nicholls used often relate how, when a child, he saw Queen Victoria on her way to the Coronation. His father was an enthusiast for Democracy and Socialism, and as a youth the future editor of "The Mercury" listened to such men as Louis Blane, Kossuth, Fergus O'Connor, Robert Owen, and others. The house, indeed, was a mark of safety for political refugees of all countries, most of whom, as Mr. Nicholls used to relate, borrowed money. It was, too, a special delight to him to recall the fact that as a boy he used to take off his hat to the Duke of Wellington, who always most punctiliously acknowledged the salute. His early schooling was at Binfield, in Berkshire, and he passed examinations in Latin and French at the London Literary Institute. For some time he lectured, and wrote for newspapers, in particular for the "Leader," the editor of which was Thornton Hunt. At the age of 23 he decided to try his fortunes in Australia, and in the year 1853 reached Melbourne. He tried various things, but eventually became editor of the "Diggers' Advocate," a newspaper printed in Melbourne, and sent to the goldfields. He was not able, however, long to resist the gold fever, and went to Ballarat, in and about which city he remained for nearly 30 years. While digging at Creswick he became local correspondent of the "Ballarat Times,"' and in 1858 was offered a position on the staff. His luck at gold digging was out st that time, and he accepted the offer of £5 a week, and left for Ballarat. His mates walked half way with him, then shook hands, and they parted, never to meet again. After two years on the "Times" he was offered the position of editor of the "Ballarat Star," which he accepted, and retained till 1883. During this period he acquired an interest in the paper. While in Ballarat he contributed many articles to the Melbourne "Argus" and 'Australasian," and was a leading figure in connection with the great Victorian constitutional crisis, his articles attracting wide notice. He achieved a reputation as an authority on constitutional questions, which had remained with him ever since. His "Bush Sermons" and "N Papers," and other articles over the norn de plume of "Henricus," were much commented upon. In 1867 he published "Politics in Verse," dealing with the political affairs of tho time. He stood for Parliament at the general election which resulted from the "crisis," but was defeated by a narrow majority. '

- In Ballarat Mr. Nicholls did a great deal of valuable work in connection with the mining industry. He was there at the time of the Eureka Stockade, but withdrew before the attack took place, because he realised that defence was hopeless, and did not approve of the methods adopted for remedying what he recognised to be hardships and injustice suffered by the miners. When the Ballarat Local Court was established afterwards to deal with mining cases, Mr. Nicholls was selected as one of the first members. It was he who first advocated that mining companies should be held responsible for accidents occurring as a result of neglect of proper precautions. He put forward his ideas in 1860, when he read a paper at a meeting of the Ballarat Mining Institute This principle was adopted by the Victorian Parliament, and later on in all the other States. It was he, too, who suggested the "no liability" system for mining companies, and kept hammering away until his efforts were crowned with success.

- In 1883 Mr. Nicholls was appointed editor of the Hobart "Mercury," in succession to the late Mr. James Simpson, and remained in that position till his death, actually writing his last leading article on Sunday. In that 29 years he did many notable things, and by his vigorous writing helped to guide public opinion through the clash of parties and the stress of political strife. "Last year he came into especial prominence through being summoned before the High Court of Australia to answer a charge of contempt of the Arbitration Court. It will be remembered that the case was dismissed, and the High Court gave a judgment defining contempt, and limiting its application, which makes The King versus Nicholls a leading case of extraordinary importance to the press of Australia. In June of last year a number of leading citizens formed a committee to arrange for a public reception to Mr. Nicholls, and the presentation of an address. The idea was taken up with the utmost heartiness, and on June 27 the Town Hall was crowded with people representative of every class in the community, who thronged there to do him honour. At the gathering letters and telegrams were read from the editors of the leading newspapers of Australia, expressing their admiration for Mr. Nicholls, and their appreciation of his work.

- Mr. Nicholls, whose wife died only a few years ago, leaves a family of two daughters and six sons, of whom Mr. Justice Nicholls is one. Two of them are in South Africa. [8]

Notes

- MR. GEORGE BLACK.

- There appeared in the obituary column of The Argus a few days ago the following notice:—"George Black, at Kew, 62 years, an old colonist, deeply regretted." A few of the few who remember the early days of the colony, and are familiar with matters in connexion with the change of policy towards the miners which followed the Stockade, read this brief notice with some solemnity and wonder, for it brought back reminiscences of olden days and there was wonder that no more was said about one who helped to make colonial history. After some inquiry, it was ascertained that the George Black referred to in the obituary notice was the person for whom the Government once offered a reward of £200 as a traitor to Her Majesty, and an instigator of rebellion. Yet Mr. George Black never was a traitor in any sense, and the only rebellion which he helped to instigate was opposition to very harsh and unwise laws. As far back as 1853 Mr. George Black became proprietor of a paper called the Diggers' Advocate, which was printed first by a Mr. Hough then at the old Banner office, in Latrobe street, Melbourne, by Mr. Hugh M'Coll, of Grand North-western Canal fame ; and afterwards at the Herald office. This paper was established, partly, of course, with the idea of making money, and partly to advocate the rights of the diggers, who were sorely harassed by "traps," licences and the general policy of the Government of the day. Mr. George Black had kept a store at the Ovens, where he made some money, and a part of that money he invested in the purchase of the Diggers' Advocate, which had been started by Mr. George Thompson and Mr. Henry Holyoake, brother of the well-known writer on Co-operation in London. Soon after Mr. Black became proprietor the editorship of this gold fields weekly was entrusted to Mr. H.R. Nicholls, now of the Ballarat Star, who had only just arrived in the colony. Mr. Ebenezer Syme, who had also only arrived a short time before, used to write one or two articles a week for the Advocate and nearly the whole of the writing was done by Mr. Nicholls and him. It is needless to say that the politics were liberal. Not, certainly, liberal in the sense in which that unhappy word is now used, for neither of the writers entertained any idea of giving all power to a chance majority of one House, but liberal in the sense that the fair representation of the people was demanded, and that there was bitter opposition to the gold-lace régime of the day, as well as to the high-handed proceedings of the authorities on the goldfields. One grand and fatal mistake was, however, made at the outset. Instead of a printing plant having been taken to the diggings, the paper was printed in Melbourne, and sent up by coach, the consequence being that the parcels were frequently left upon the road, and some-times disappeared altogether. This I believe, prevented the Advocate being a grand success, because it could not compete with the papers which were started on the gold-fields, and after some few years it was stopped. Mr. George Black was at Ballarat at the time of the Eureka outbreak, which he did something to bring about, but he was not in the stockade at the time of the attack, and I do not think that he had been there for some days before it. He was, I know personally, very doubtful as to the success of the movement. The proclamation — a very wordy and initiated one — which was read to the "troops" was not written by Mr. George Black, but by his brother, Mr. Henry Black, who was afterwards killed by the unexpected explosion of a blast whilst quartz-mining at Staffordshire Reef. Mr. Henry Black was not endowed with literary powers, and he was fully aware of the fact, and he therefore asked the present writer to draw up a proclamation for him, which the said writer, for prudential and other reasons, declined to do. The proclamation was therefore read as it was first written, and I need only say that its style and matter would not be out of place in some of the manifestoes of the new-light "liberals" of the present day. After the stockade affair had fairly been squelched by the prompt action of the Go-vernment forces, Mr. Black remained in hiding for some considerable time, but again resumed active connexion with what was then called the Gold-diggers' Advocate, a title adopted to prevent any dispute as to implicated interest in the old Diggers' Advocate. Through the columns of his paper he advo-cated many of the reforms which have now been made, but he was unpopular because he opposed the reduction of the postage on inland letters from 6d. to 2d., his contention being that the smallest of coins then in general use was not too much to give for the postage of a letter. However, the Advocate under both its names did not live many years. It was planted in the wrong place, could not hold its own against the gold-fields papers which gathered their news in the place of publication, and, as it were, gave it to their readers hot and hot. After-wards Mr. George Black betook himself to mining pursuits, or, rather, to speculation, with, I believe, no very great success. For many years his name has not been heard of as a public man, and there are probably few who know how much his early labours con- tributed to bring about one of the most pro-minent events in the history of this colony. Mr. Black never possessed the arts which make public men very popular, and in Ballarat he did not secure the support of the miners, whom he had certainly served as well as many to whom they gave a more generous recognition. In 1850 he contested Ballarat East with Mr. J. B. Humffray and Mr. Thomas Loader, and the result of the poll was as follows:— Humffray, 690 ; Loader, 255 ; Black, 24. From this it will be seen that the goldfields advocate was not so popular as a stranger from Mel-bourne, although the capture of the advocate had been valued at £200 by the Government, whilst £500 had been offered for the capture of Vern, who somehow obtained a promi-nence which he did not in the least deserve. The bill issued by the Government set forth that "whereas two persons of the names of Lawler (sic) and Black, late of Ballarat, did, on or about the 18th day of November last, at that place, use certain treasonable and seditious language, and incite men to take up arms with a view to make war against Our Sovereign Lady the Queen," &c. No doubt strong language was used, and no wonder, but it may safely be said that Mr. George Black was as little of a rebel or a demagogue as could be found south of the line. The voting in Ballarat East showed that he had not made such an impression as either Mr. Humffray or Mr. Lalor; and I, who knew him well in his best days, can testify that he had all the instincts of a gentleman, with few of the qualities by which vulgar popularity is won. However, he was not quite so unpopular with the voters of Grenville as with those of Ballarat East, for he was very nearly elected for the former place. Indeed, Mr. Black was the victim on that occasion of a very unpleasant sell, or of too much confidence. In those days the telegraph was not available to allay the anxiety of candidates, and the returns from the various polling places, some of them 10 miles apart, had to be brought in by horse-men, over roads which only those who have seen them can appreciate. On this occasion the roads were very bad, the country was almost a swamp, and the day was cold, dark, and wet. Mr. Black was at the central polling place, the Crown Hotel, Buninyong, anxiously awaiting the arrival of returns. As they came in, he and his friends grew more and more elate, and finally matters appeared to them all to be so satisfactory that Mr. Black was induced to go out on to the bal-cony and return thanks for having been elected. All his supporters departed home in high spirits, but when the complete returns came in it turned out that there was a good majority against him, and his thanks had been premature. This event may be said to have concluded Mr. Black's public life. As far as I am aware, he never contested an election again, and took little or no part in political strife. His period of activity extended from 1853 to 1860, or thereabouts, and those who have grown up since then may well wonder who Mr. George Black was, and feel surprise at the memories which the news of his death recalls. The old ones — those who made the colony what it now is, or rather what it once was — were young in those days, full of the spirit of adventure, and keen to face wrong and assert the right. If there is a charm in saying "We twa hae paidl'd i' the burn," is there not a tenfold one, a sense of mournful pleasure, in remembering how we stood together in the days when all was strange and new — save the folly of rulers, which is as old as the hills — and when fortune was all before us, and memories of home were still keen and clear? Thus it comes about that the few words which I have quoted from the obituary column illumined a track long passed over, recalled some events only to be found recorded in the history of Ballarat, and some which cannot be found there at all. Thus it is, also, that I deem that a man like Mr. Black ought not to be allowed to pass away without some record of his work and some tribute to his memory, as one who did his best, and one who did that best con-scientiously. As far back as 1853, he was seriously ill with disease of the lungs, and never had the bold energy to become a popu-lar favourite ; and that he lived so long after his first attack was a matter of wonder to many. He has gone at last, another of that band of enterprising men who made this colony a marvel to the nations, and who showed an aptitude for self-government and peaceful settlement never equalled in any other period of the world's history.

H. R. N.[9]

Notes

- OLD TIMES ON BALLARAT

- No. 7. THE OLD LOCAL COURT ELECTIONS BY "SILVERPEN."

- All old Ballarat will remember the local court, and the great fun and frolic in dulged in by the friends of the candidates for a seat in that embryo mining Parliament. As is always usual with would be legislators for either a thinking board or Leglslative Assembly, promises are plentifully given, and the slightest wish of the interrogatory voter, as a matter of good policy, acceded to. At one election Dr Kenworthy, long since dead, was a candidate, and but for the. manoeuvres of Carboni Raffaello (“Great Works"), he (Dr Kenworthy) would have certainly been elected. In those days the gentlemen of the medical profession were not so full of business as one might expect, But the fact was, there was comparatively little sickness; and this worthy American “medico,” as a consequence, took to the life of a seeker, for the precious racial, and with rd shirt, moleskin unmentionables, and plenty of “ Yankee blarney, and was pretty successful, both as a gold digger and a popularity, hunting adventurer. The “blarney,” in dealing with the "digger mob” of those early days, was an essential, and served the doctor instead of logic. It was not, therefore, very surprising that the diggers heard him gladly, and drank his jolly good health in bumpers of bottled ale at their own expense. Although a digger, and always in digger costume, Kenworthy was invariably called “Doctor,” and when at the Eureka Stockade he was appointed medical officer to the insurgent forces the expectant warriors for diggers' rights rejoiced exceedingly. On the day. Kenworthy stood as a candidate the morning was ushered in by many a shout at the grog shanties on the flat. Warden Daly (since dead) occupied the chair on the temporary platform erected on Bakery Hill, and a big crowd of the Eureka boys assembled to give their votes. The doctor addressed the assemblage In his usual “streak of lightning” style, and was duly proposed as a fit and proper person to fill the position of member of the Local Court. Everything seemed favourable and we ell expected the doctor right for election, when up jumps “Great Works, his repulsive face, fiery red beard, and ferret-like, wicked eyes sparkling with envy and hatred, gave the assembled voters the cue that Carboni Raffaello meant mischief. He went off like a sky-rocket, denounced the doctor as a “spy and a traitor,” and de clared that when he (“Great Works”) was taken as a prisoner to the camp by the lousy “traps,” he there saw the doctor, disguised “vith a vig ” and false beard, pointing out to the blasted camp officials the principal rioters in the rebel camp; and thus acting the “double villain” by fawning on' the boys at the Stock ade and selling them like a traitor in the camp. As this was spoken by “Great Works” in the most bitterly sarcastic and spiteful way, you may judge the effect it had on the crowd of excited diggers, “Blood-un ’ouns !” says Pat Malone, “just let me at the doctor shpy, and if I don't lave him so that bis own mother won’t know him, nor Dr Bunce be able to hale him for the next month, then chuck me down the first shicer we come to on our way to the flat.” A general howl of execration followed this impromptu delivery, and the doctor thinking discretion the best part of valour, amidst a storm of groans and boo-boos, and cries of “ Traitor," made his way over the hill, and cleared for his canvas home completely flabbergasted. The result was, as might have been anticipated, “ Great Works" was elected by a big majority; show of hands being the mode of voting. At another election W. C. Weeks, afterwards member for the Ovens, and now dead, stood up to propose a well-known digger named Kennedy, aftas “Lickln the Lag,” so called from his having at one of the meetings prior to the fight made use of the following poetic couplet:— Moral persuasion Is arrant humbug; Nothing convinces like a lick in the log; Kennedy, although well known, was not well liked, for during the battle twas said be had shown the white feather, and altogether was not the man to fight when there was a chance of running away, and this peculiar weakness of his was freely commented upon by the survivors of the fight la consequence of his failing he (Kennedy) was not popular, and as soon as Weeks proposed him the cry arose, “Stand yourself; you’re the better man; we’ll vote for you. Weeks, Weeks, Weeks!" was echoed and re-echoed by the crowd. “Oh,” said “Oily Charley," “gentlemen, if you prefer me to my friend Kennedy, I cave in at once, and bow to the decision of your better judgment." The warden (Daly), there fore put the motion that Weeks was a fit and proper person, &c., &c., and the rising of a forest of hands told Weeks he, not his friend, was elected. Charles bowed his thanks, and retired, seemingly altogether oblivious of his duty to Kennedy, whom he was pledged to propose and support. Poor Weeks, after being rejected for the Ovens on presenting himself to that constituency a second time, eked out a precarious living for years at lecturing and acting as Melbourne correspondent for the Ovens and Murray and some years ago died suddenly In Melbourne, neglected and uncared for by many whom he had in his time be friended, for he was in his day like many other members, “ a capital billet-getter.” It will be remembered that after leaving Ballarat, and before being returned for the Ovens, he held some menial position on the Government railways, and always said it was for this cause he was snubbed by many of the members of the House, who thought when returned to Parliament that they were at once transmogrified into gentlemen. H. R. Nicholls, of Ballarat, and John Wall, of Sebastopol, are the only members of the old local court, I believe, still residing amongst us. James Baker, the first chairman of the board, is now in New South Wales to a good billet under that Government, and I heard only recently has still the old “ Ballarat fire*’ in him, as shown in the early days of the gold diggings, when he gained the goodwill of the miners, and worked energetically and well for the righting of local grievances in the old Local Court.[10]

See also

Further Reading

Corfield, J.,Wickham, D., & Gervasoni, C. The Eureka Encyclopaedia, Ballarat Heritage Services, 2004.

References

- ↑ Hobart Mercury, 14 August 1912.

- ↑ http://www.chartists.net/Chartists-in-Australia.htm

- ↑ Wickham, D., Gervasoni, C. & Phillipson, W., Eureka Research Directory, Ballarat Heritage Services, 1999.

- ↑ Centennial Magazine, May 1890.

- ↑ Launceston Examiner, 14 August 1912.

- ↑ Wickham, D., Gervasoni, C. & Phillipson, W., Eureka Research Directory, Ballarat Heritage Services, 1999.

- ↑ Sydney Globe, 21 August 1912

- ↑ Hobart Mercury, 14 August 1912.

- ↑ The Argus, 19 April 1879.

- ↑ Ballarat Star, 0 February 1881.

External links